Indians On Tour

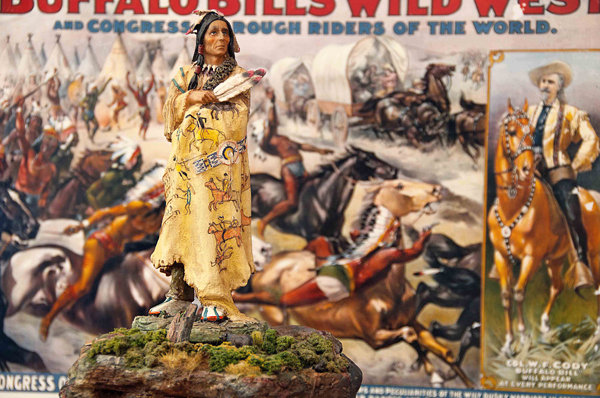

Indians on Tour began in 2000 when friend and documentary film maker Ali Kazimi sent me a package with five plastic Indian figures and one cowboy—two of which Ali used to introduce his documentary film on my work “Shooting Indians: A Journey with Jeff Thomas.” Along with the figures was a note that said: “You will find something interesting to do with them.” On my next photo walk in Ottawa I put one of the plastic Indians in my camera bag and returned to a previous site where I had photographed a bronze statue of an Indian hunter. I placed the plastic Indian in front of the bronze Indian and when I saw the photograph I was intrigued by the juxtaposition and the multi-layered meanings. The plastic figures become markers of childhood games of “cowboys and Indians” based on TV shows and movie westerns, of souvenir shop stereotypes, and of historical re-enactment parks found at Frontier Town and Euro-Disney. They also reference the Native people who went “on tour” in these early historical re-enactments like the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show. Yet the photographs reverse the typical pattern of tourism. The Indian figures now visit popular non-Native tourist sites of North America and Europe.

View the other Portfolios from this series:

MY NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN VOLUME 21

MY NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN VOLUME 22

2018 SERIES (2000 – 2018)

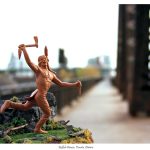

Ottawa, Ontario, “War Dancer, Hunter Statue, Queen Street,,” Nov. 26, 2000. 45.4223,-75.696717 | TRAVELOGUE: The War Dancer was the first Indian figurine I posed in the everyday world and I chose the Indian Hunter statue to pose War Dancer. When I saw the print I was intrigued by the latitude the figure provided me in my quest to intervene and define urban spaces from an indigenous perspective. I had never seen such an approach and it added to my ongoing scouting trips in search of Indian figures used on monuments and architectural decorations.

Toronto, Ontario, “Peace Chief, CN Tower, Bathurst Street Bridge,” 2003. 43.6402, -79.40105 | TRAVELOGUE: The Peace Chief was photographed near Fort York (the city’s birth place) on the Bathurst Street Bridge with modern day Toronto in the background. The Peace Chief wanted to go ride up to the top of the CN Tower because he wanted to touch the clouds.

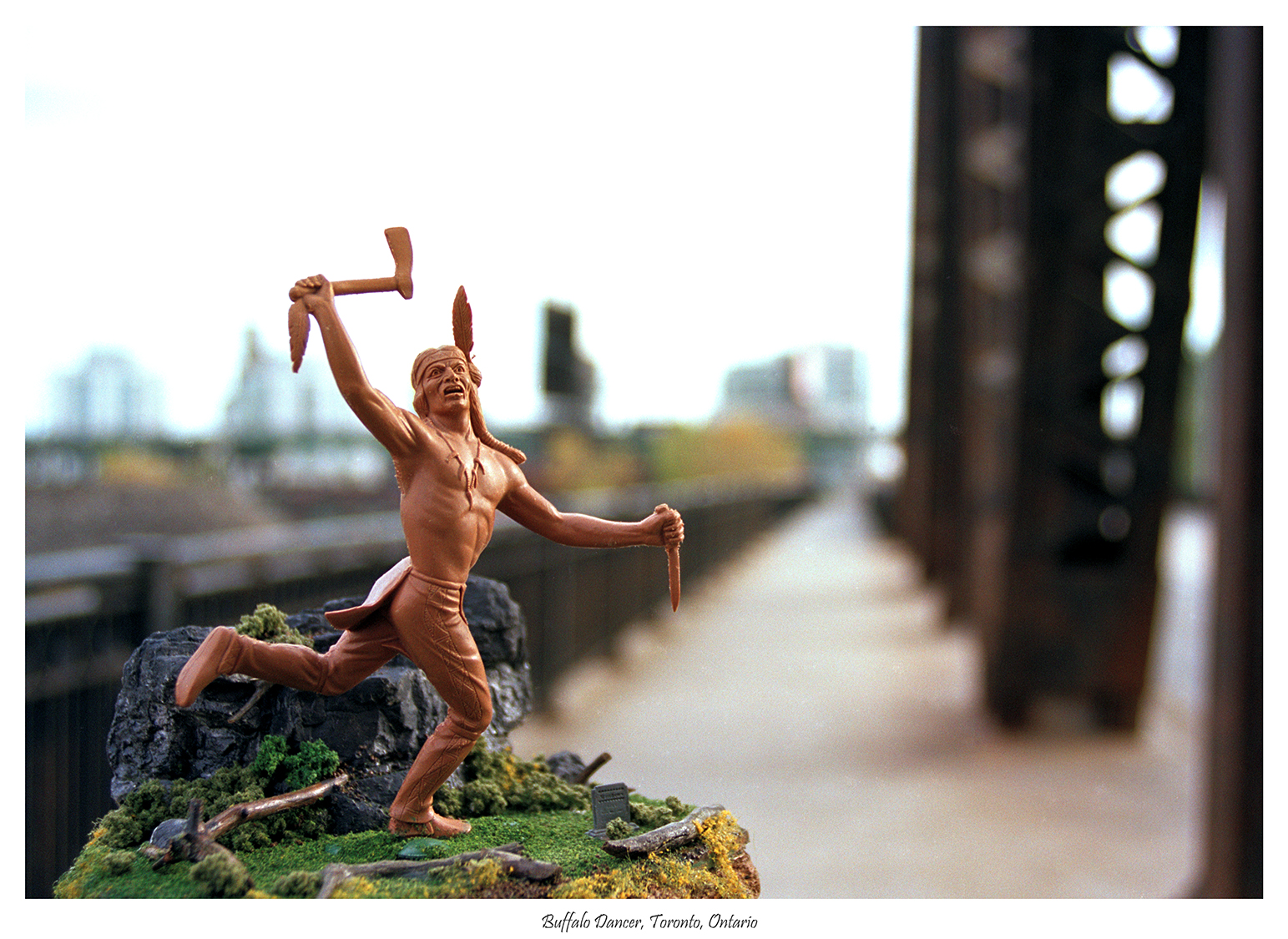

Toronto, Ontario, “Buffalo Dancer, Bathurst Street Bridge,” 2003. 43.6402, -79.40105 | TRAVELOGUE: Travelogue – Buffalo Dancer accompanied me on a road trip to Toronto. “Did you know that Toronto is an Iroquois word – Tkaronto?” he asked. “We had two Seneca villages here around the 1660s, Ganatsekwyagon was on the banks of the Rouge River and Teiaiagon was on the banks of the Humber River. The Seneca returned to Iroquoia [New York State] after the beaver trade began to collapse.”

Ottawa, Ontario, “Chief Red Robe, North American Indian,” 2005. 45.4128, -75.61168 | TRAVELOGUE: I remember the time when I was a kid and travelling over the Peace Bridge to Canada and the customs officer asking my grandparents their citizenship – they replied North American Indian. I realized that I was different from the kids I went to school with who recited the Pledge of Allegiance without question, at the beginning of each school day. I wanted to commemorate my childhood memory and my opportunity emerged when I found a North American Van Lines trailer parked.

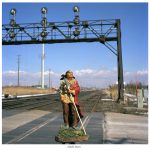

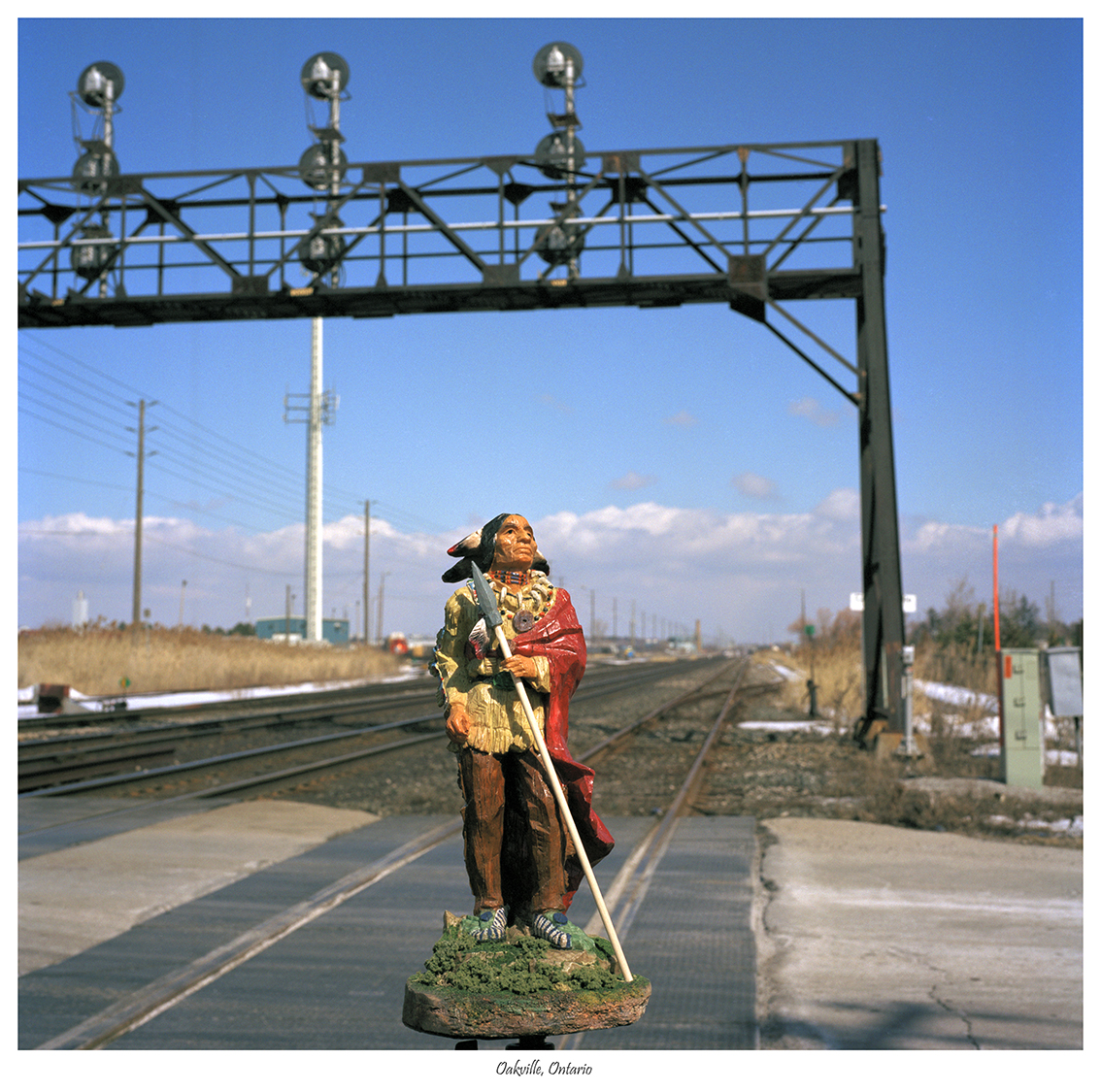

Oakville, Ontario, “Chief Red Robe, Waiting for a Train,” 2006. 43.49003, -79.65376 | TRAVELOGUE: Chief Red Robe and I were on the road, searching for new railroad sites for my railroad series The First Spike. During a visit to Regina, Saskatchewan, I met a woman who told me a story about a local Indigenous man who used to dress in his tribal clothing and stand by the tracks. He wanted people stopping at the train stop, to know that his ancestors gave up their land for the transcontinental railroad. Chief Red Robe liked my story and he agreed to pose for me.

London, England, “Chief Robe, King Street to Covent Gardens,” 2006. 51.51139, -0.12526 | TRAVELOGUE: While in London, England I took the opportunity to follow the same street the Four Indian Kings walked down in 1710. I was in London to attend an opening for an exhibition I was in, showing my version of the Kings, with the original four large portraits of the Four Kings painted by the Dutch painter Jan Verelst. I imagined what it must have been like walking down the street with them and onlookers gawking and laughing at the exotic Indians.

Craigellachie, British Columbia, “Northern Plains Chief,” 2007, Site of the Last Spike. 50.97471, -118.72375 | TRAVELOGUE: While on a road trip from Vancouver to Lethbridge, Alberta I had my first opportunity to visit the site where the last spike was hammered in, completing the transcontinental railroad. It was a moment of introspection and considering the role of Northwest Resistance led to funding the completion of the disputed railroad.

Gatineau Park, Quebec, “Chief Red Robe, Champlain Lookout,” 2009. 45.50818, -75.91284 | TRAVELOGUE: When I posed Chief Red Robe at this majestic site I was thinking of the Indian figure that used to kneeling at the base of the Samuel de Champlain monument in Ottawa. When I met the Scout in the Fall of 1992, I asked him: where would you go if you could leave this place. He represented the 16th century world and returning home would be challenging in the 21st century. I told him I would start scouting sites for him to visit when he would finally be able to leave.

Chicago, Illinois, “No Pipe, Michigan Avenue Bridge,” June 3, 2009. 41.88836, -87.62483 | TRAVELOGUE: I had seen the bas-relief sculpture on the Michigan Avenue Bridge, on a television show and decided I had to see it for myself. After several decades I finally visited Chicago and during a tour bus ride through the city, saw the The Battle of Fort Dearborn, a battle between American and the Potawatomi tribe, commemorated on the site of Fort Dearborn with Defense, a sculpture by Henry Hering on the south eastern tender’s house of the Michigan Avenue Bridge.

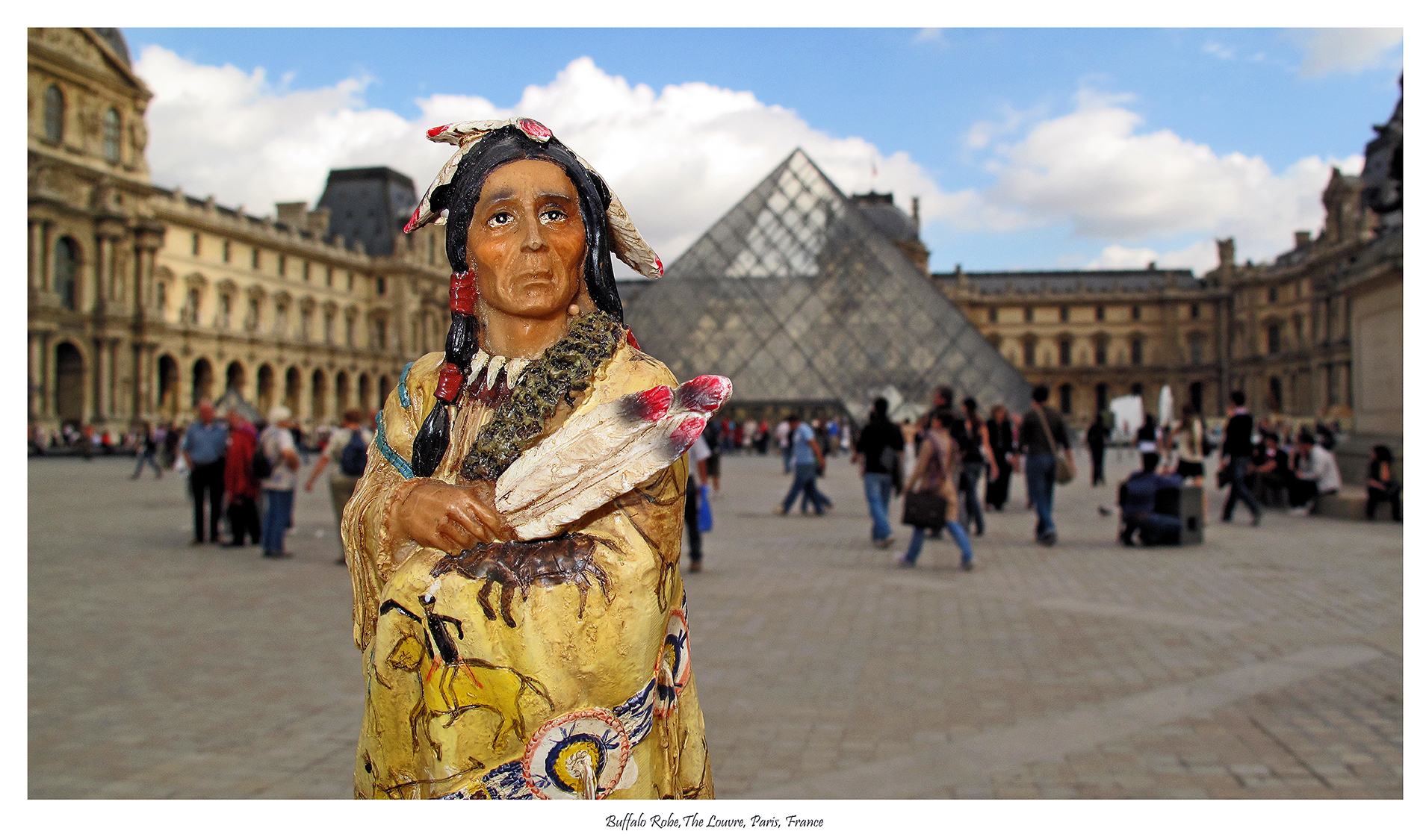

Paris, France, “Buffalo Robe, Louvre Museum,” 2010. 48.86061, 2.33764 | TRAVELOGUE: Before entering the Louvre, I posed Buffalo Robe as a tribute to the Indigenous performers who took part in George Catlin’s Indian Gallery tour and its performance at the Louvre in 1845. The dancers with Catlin were Ojibway from southern Ontario, led by Maun-gua-daus (aka Great Hero, aka George Henry). During the dance troupe’s European tour Maun-gua-daus’s wife and three of sons died.

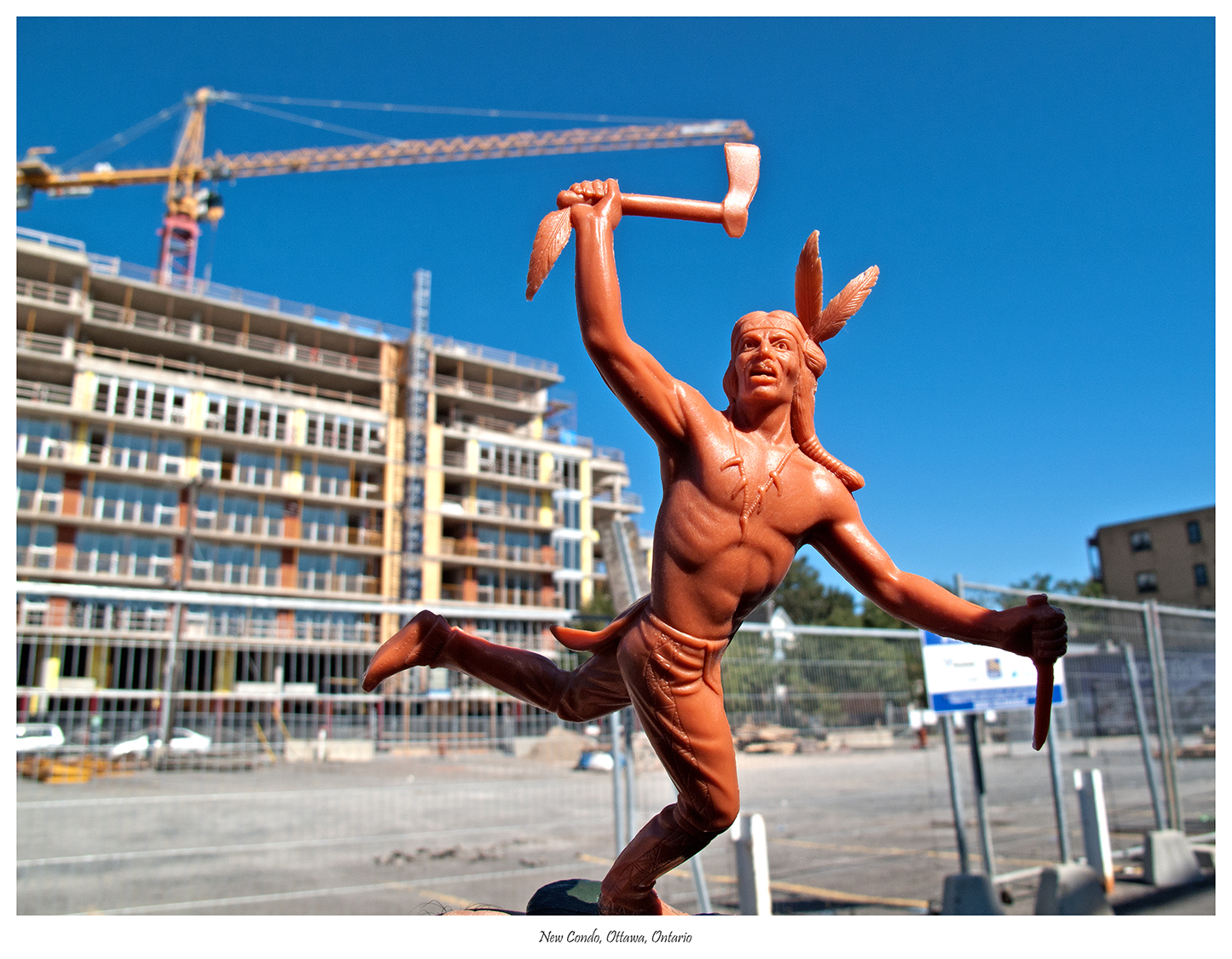

Ottawa, Ontario, “Buffalo, Dancer, Condo Construction Site,” 2011. 45.41178, -75.69306 | TRAVELOGUE: Bank Street, 2011, Ottawa, Ontario, GPS: 45.411151, -75.692822

Buffalo Robe and I were driving south on Bank Street and passed by a building site. I explained to him that a developer was putting up a new condominium. Buffalo Dancer asked: “Is a developer like the government people who came to buy our lands?” I said, yes, a contemporary version. Buffalo Dancer asked: “Will they let Indians live there?”

Ohio, “Buffalo Robe, Serpent Mound State Park, 2015. 39.02506, -83.43 | TRAVELOGUE: Serpent Mound is the world’s largest surviving effigy mound – a mound in the shape of an animal – from the prehistoric era. Located in southern Ohio, the 411 metres long (1348 feet long) Native American structure has been excavated a few times since the late 1800s, but the origins of Serpent Mound are still a mystery. Some estimates place the construction of the National Historic Landmark – also called Great Serpent Mound – at around 300 B.C.

Ohio, “Buffalo Robe, Serpent Mound State Park, 2015. 39.02506, -83.43 | TRAVELOGUE – TRAVELOGUE: The most predominant theory is that the Serpent Mound represents a giant snake, which is slowly uncoiling itself and about to seize a huge egg within its extended jaws. However, there are many theories abound suggesting various interpretations. For instance, some think it may represent an eclipse, or the phases of the moon. Others have speculated that it represents the myth of the horned serpent found in many Native American cultures.

Ohio, “Chief Red Robe, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park,” 2015. 39.37611, -83.00639 | TRAVELOGUE: Hopewell Culture National Historical Park is a United States national historical park with earthworks and burial mounds from the Hopewell culture, indigenous peoples who flourished from about 200 BC to AD 500. The park is composed of six separate sites in Ross County, Ohio, including the former Mound City Group National Monument. The park includes archaeological resources of the Hopewell culture. It is administered by the United States Department of the Interior’s National Park Service.

Ohio, “Hopewell Culture National Historical Park,” 2015. 39.37611, -83.00639 | TRAVELOGUE: This particular geographic location appears to be one of the few dedicated areas specifically for internment. Unlike other prehistoric sites found in the state, the mounds found here were almost exclusively part of a burial complex.

Unlike other earthworks, the Mound City burial complex, is surrounded by an embankment that is only 2.5′ – 3′ in height that encloses over 15 acres with 23 mounds of varying heights. It has one of the greatest concentrations of Hopewell burial mounds known today.

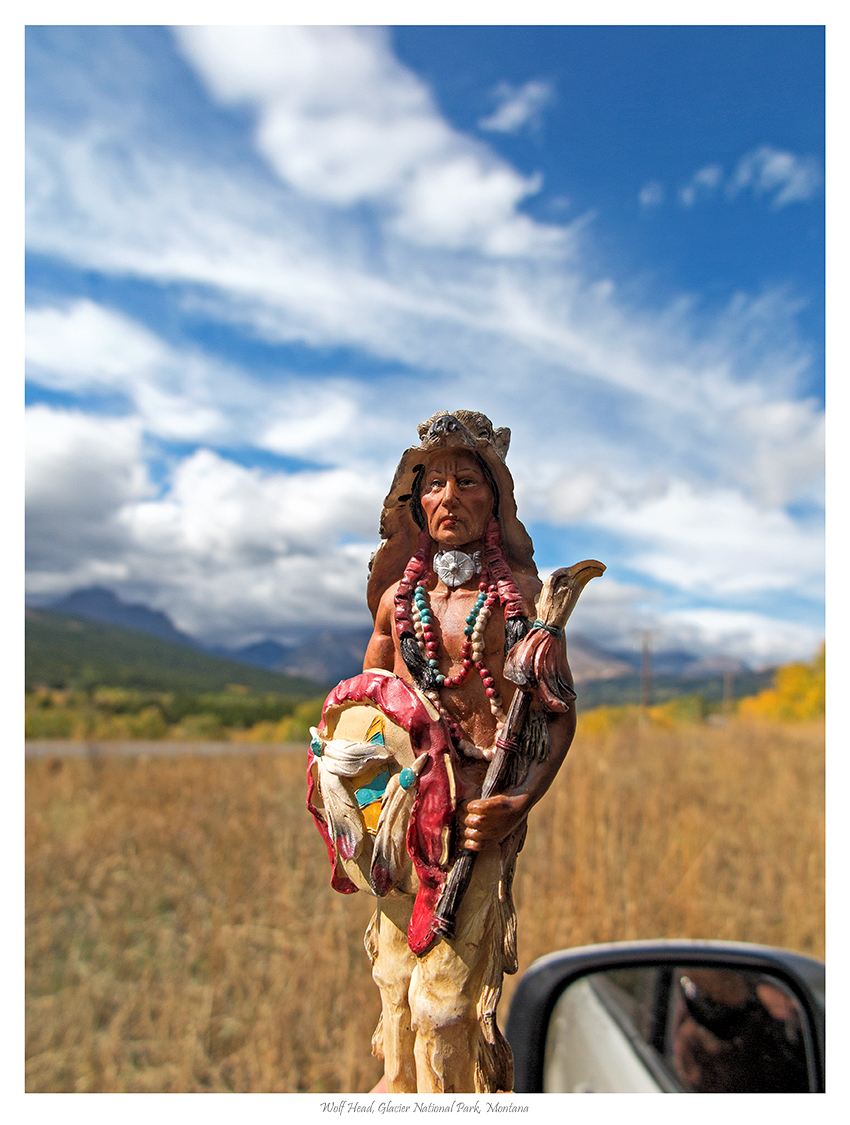

Montana, “Wolf Head, Glacier National Park,” 2015. 48.69779, -113.70656 | TRAVELOGUE: While on our way to the Blackfoot reservation, we passed through Glacier National Park. Many years ago I had dreamed of being in the mountains where I met the birdman in a cave. I was lying on a slab of rock, where Birdman met me and healed my broken body. He said to remember the sky and clouds.

2014 SERIES (2001 – 2011)